Whitney Plantation: A Place of Truth, Pain, and Remembrance

Chapel at the Whitney Plantation, sculptures by artist

Whitney Plantation: A Place of Truth, Pain, and Remembrance

A Visit I Knew I Had to Make

A few days ago, we celebrated Juneteenth, a day that commemorates the end of slavery in the United States, when the last enslaved people in Texas finally learned of their freedom in 1865. Living in New Orleans for six months, I’ve soaked in the music, the parades, the joy that pulses through this city. But there was one place I knew I needed to visit, no matter how painful it might be.

The Whitney Plantation is not like other plantations in Louisiana. It does not romanticize the past. It does not turn history into a backdrop for weddings or leisure. Instead, it confronts the truth of slavery with honesty, reverence, and sorrow. It honors the people who endured it, especially the children. And asks us to do the same.

A Museum Like No Other

The Whitney Plantation is the only site of its kind in Louisiana, and one of very few in the United States, dedicated entirely to telling the history of slavery from the perspective of the enslaved. Not the plantation owners. Not the architecture. But the people. The children. The families. The lives interrupted and destroyed.

From the very beginning of the tour, you understand this is not about nostalgia or romanticism. It’s about reckoning. About facing what really happened on this land. The Whitney makes it impossible to look away.

A Plantation with a Long History

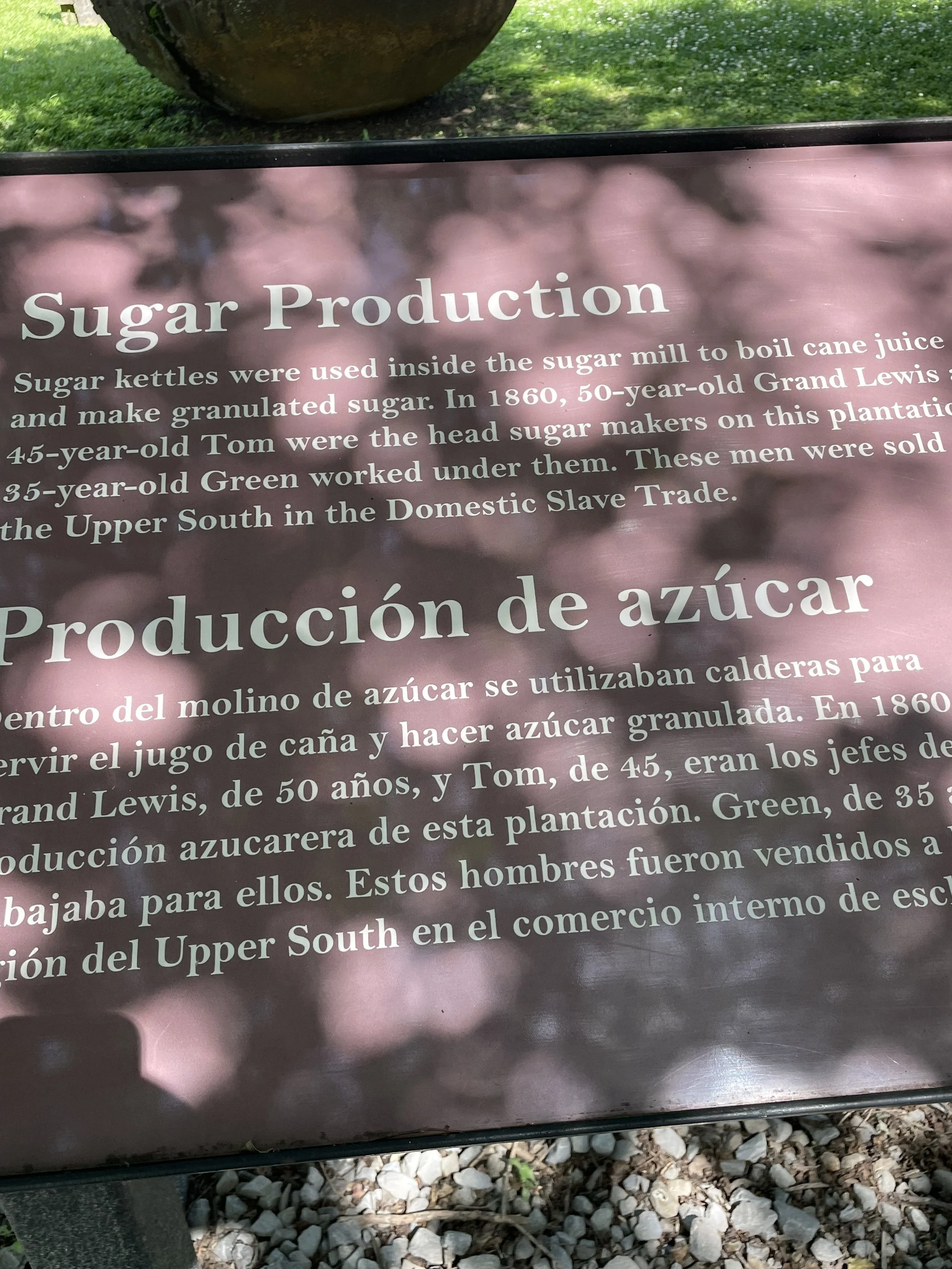

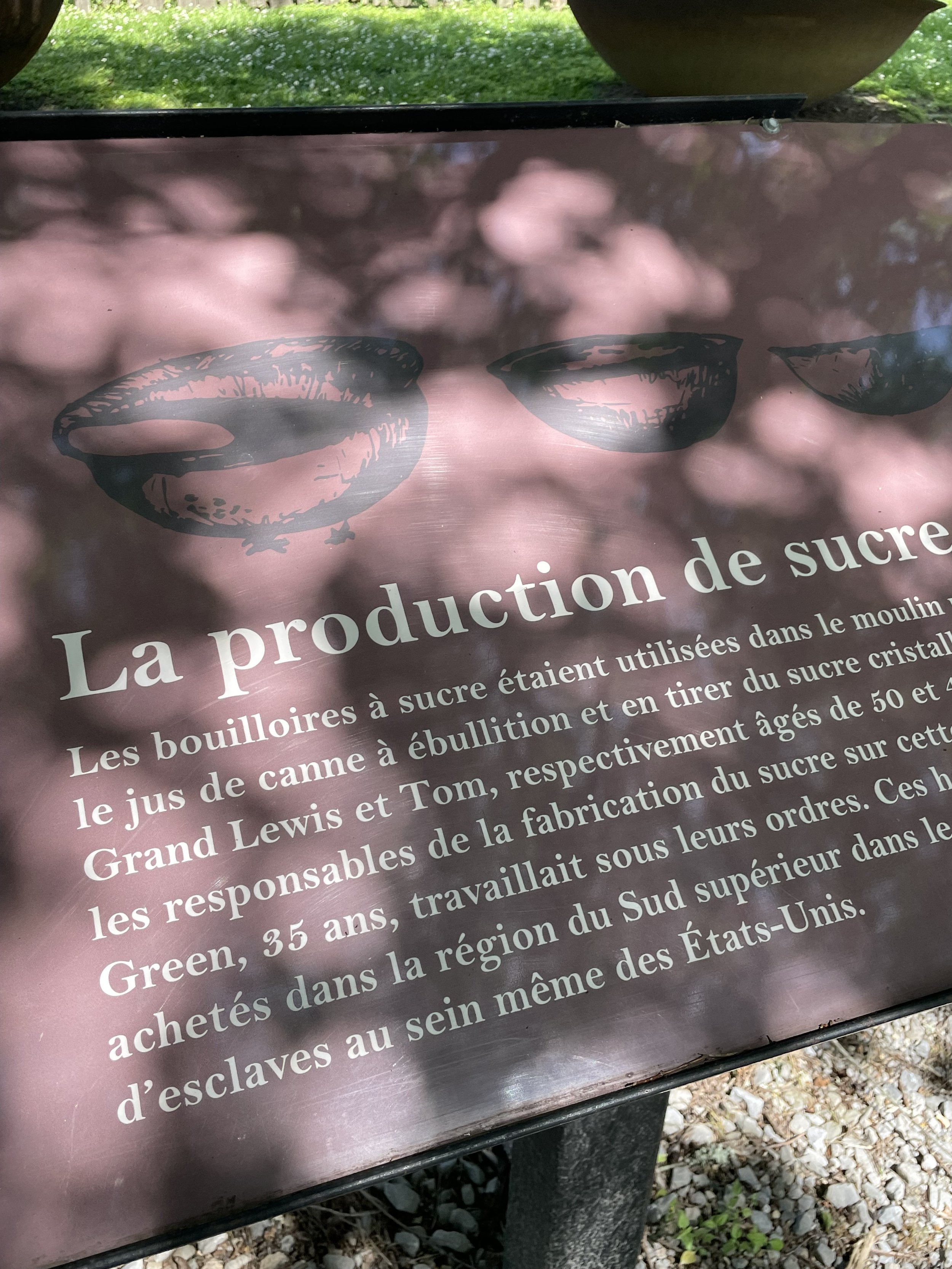

The Whitney Plantation, originally known as Habitation Haydel, was established in 1752 by German immigrants who settled along the Mississippi River. Over time, it grew into a large sugar, indigo, and rice plantation, one that relied entirely on the forced labor of enslaved Africans and their descendants. More than 350 people were enslaved on this land during its operation.

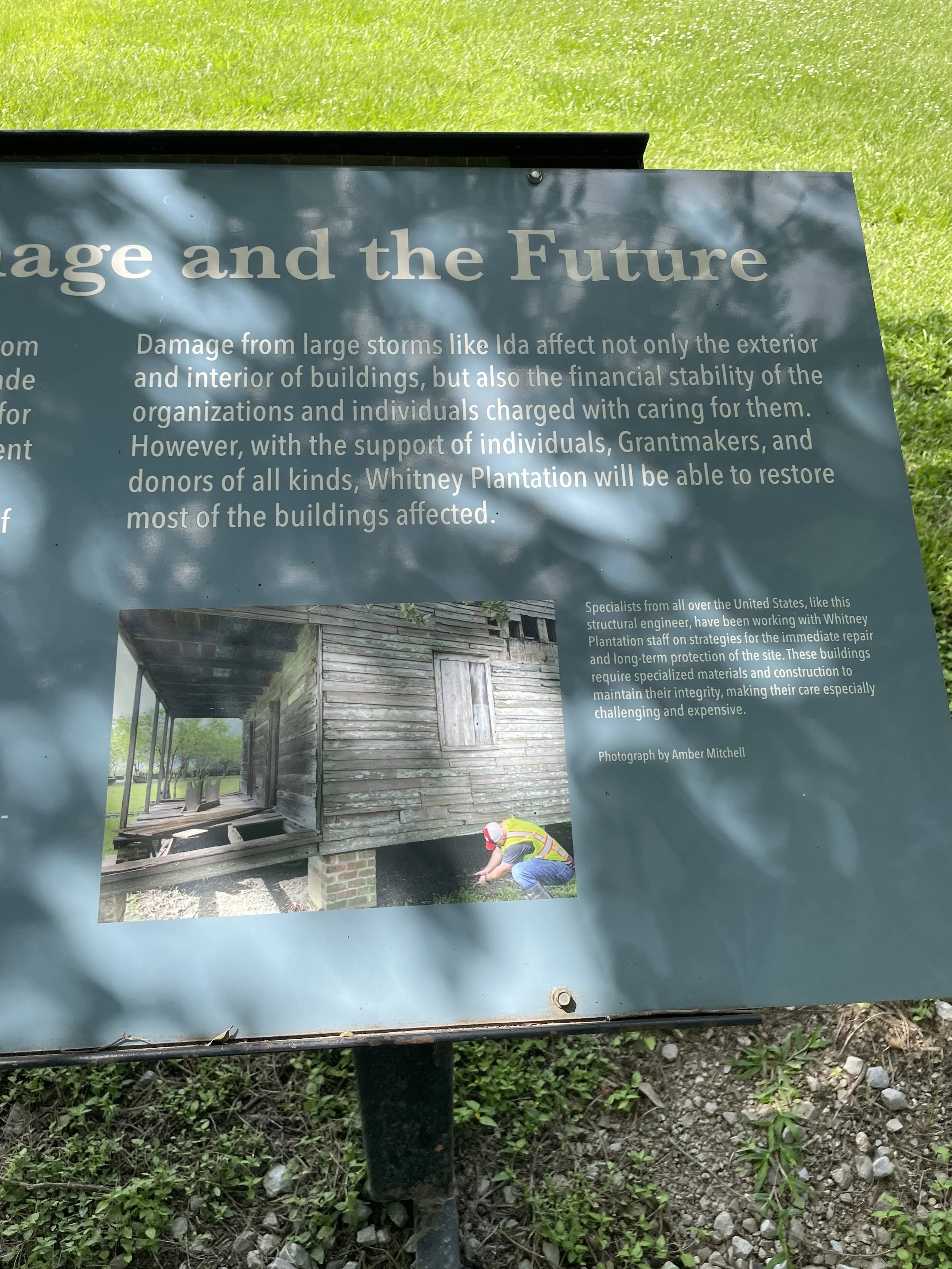

In 2014, the site reopened as the Whitney Plantation Museum, after years of research and preservation led by attorney and founder John Cummings and Director of Research Dr. Ibrahima Seck. Today, it stands as the first museum in the United States devoted entirely to telling the story of slavery from the perspective of the enslaved themselves.

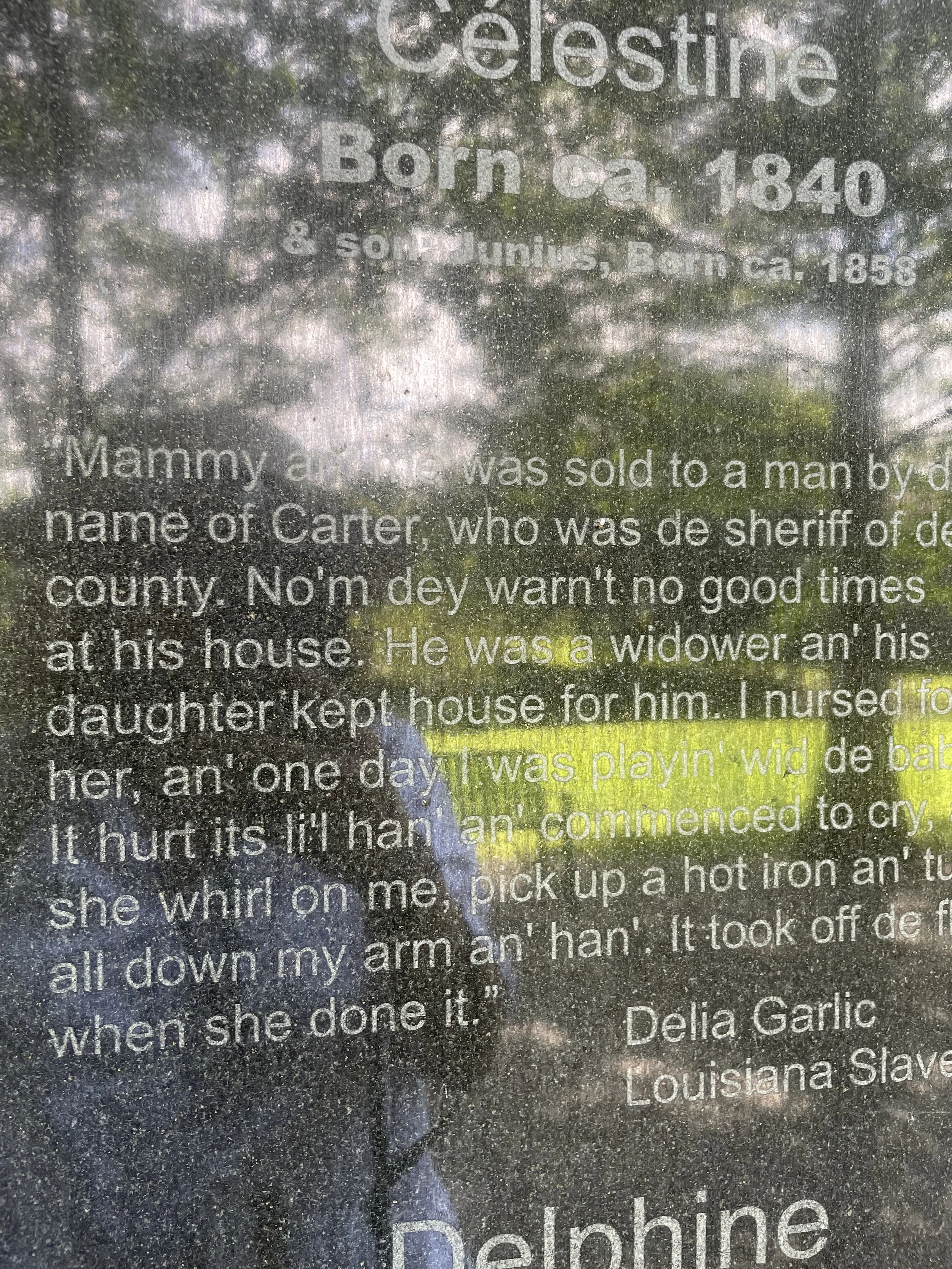

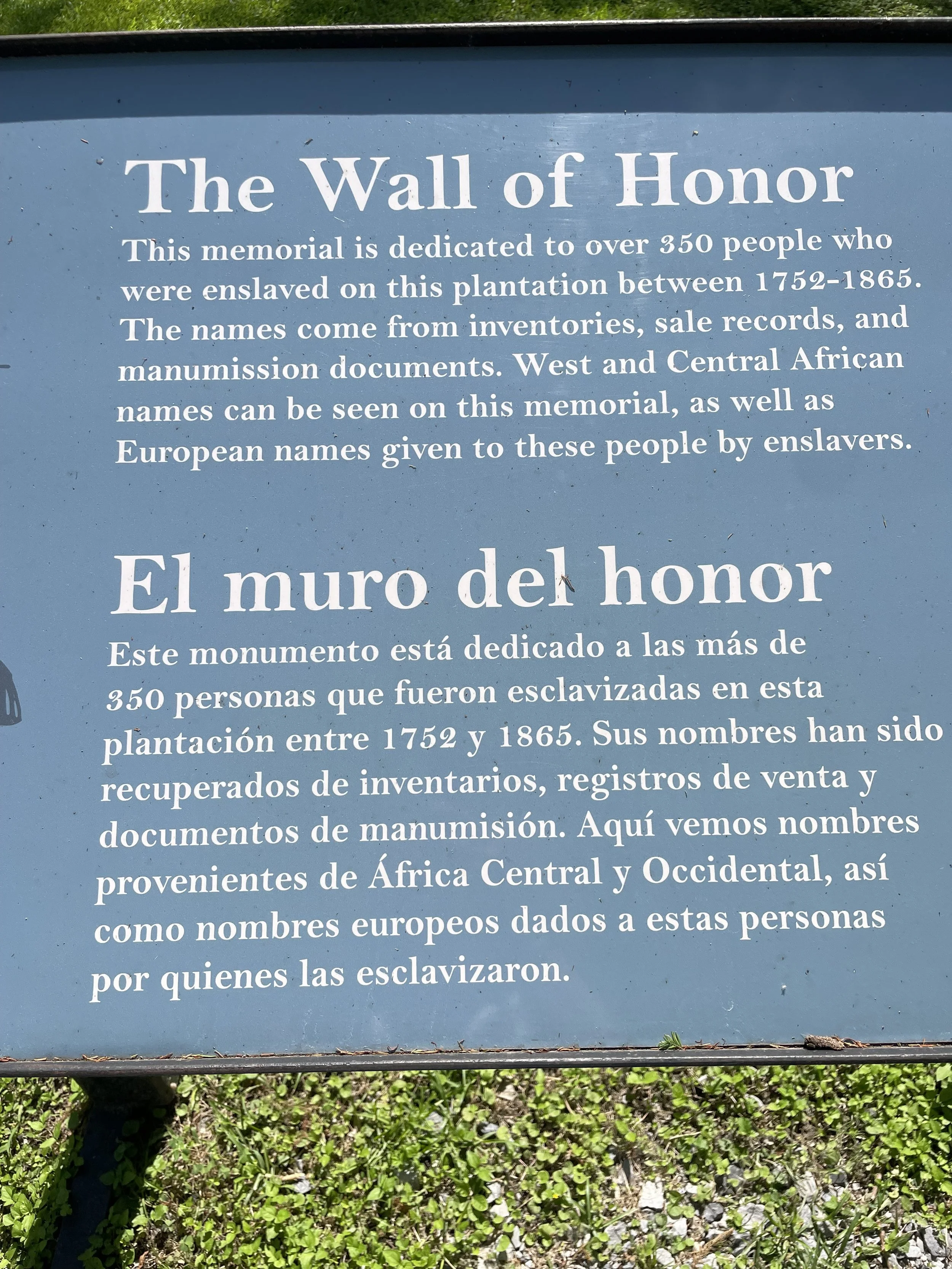

The Wall of Honor

One of the most powerful places on the grounds is the Wall of Honor, a memorial listing the names of every person known to have been enslaved at Whitney Plantation. Standing in front of those names, etched into stone, you feel their presence. They were mothers, fathers, children, skilled workers, musicians, cooks, not anonymous laborers. People with hopes and love and pain.

Reading those names, hundreds of them, you begin to grasp just how many lives were impacted. Not just over a few years, but across generations.

The Voices of the Past

The audio guide at Whitney is remarkable. It includes first-person narratives from formerly enslaved people, men who survived, grew old, and shared their memories in interviews recorded as part of the Federal Writers’ Project in the 1930s.

Hearing them speak, hearing their voices, their stories, their pain and strength is indescribable. These are people who were alive just decades ago. People whose stories were almost lost. Their voices add a dimension of humanity that no textbook can replicate. These are not distant histories.

The Heat, The Land, The Labor

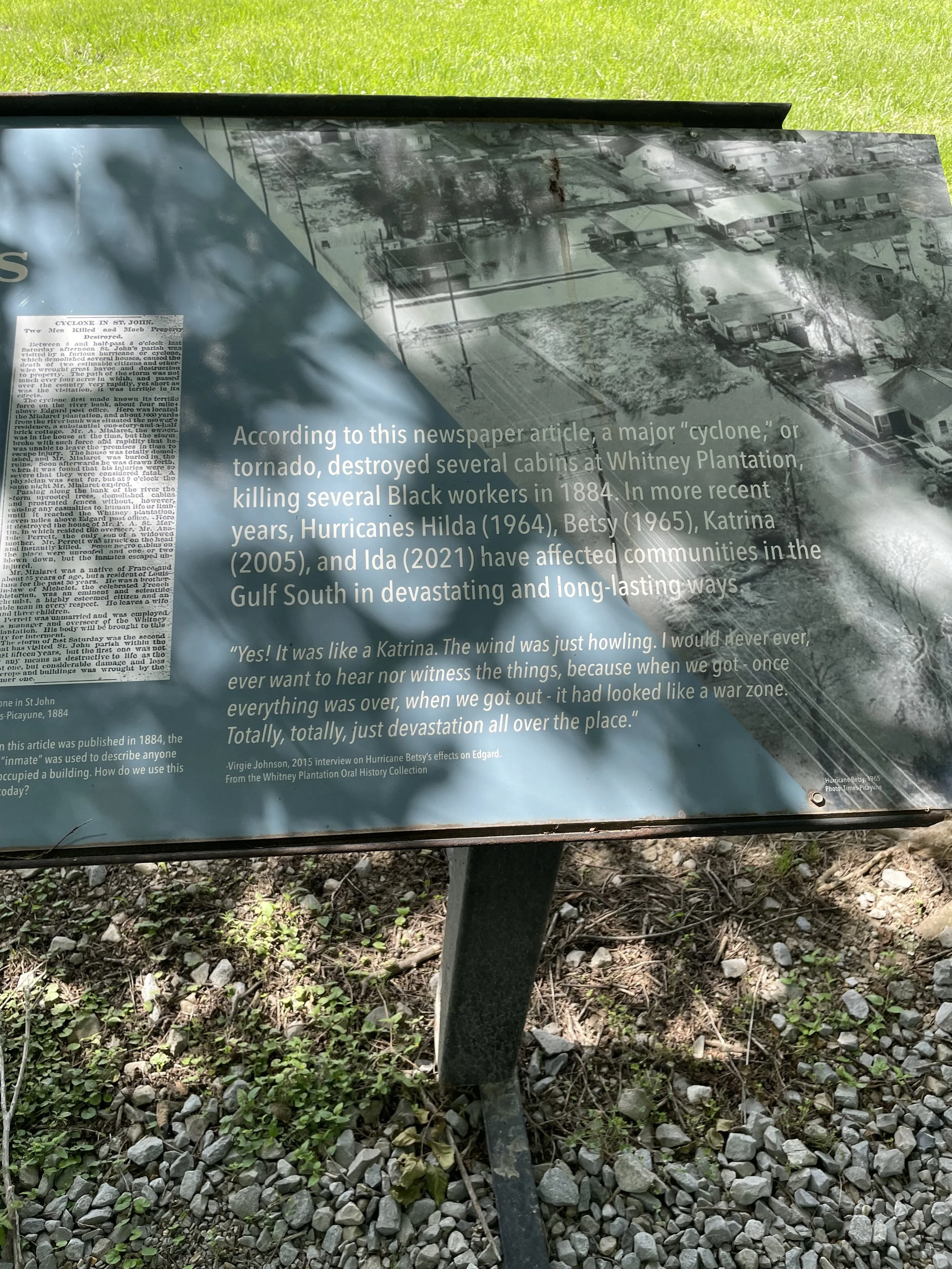

Walking through the grounds of Whitney, you feel the heaviness of the land. Even in spring, the southern heat is thick and unforgiving. The humidity clings to your skin. Storms pass quickly but violently. And in winter, bitter cold snaps arrive without mercy.

The people enslaved here worked through it all. Planting, harvesting, cooking, building. Under the blazing sun. In the mud. In the cold. The physical toll is impossible to imagine. And yet they endured. They resisted. They loved. They carried each other.

The Houses: Two Different Worlds

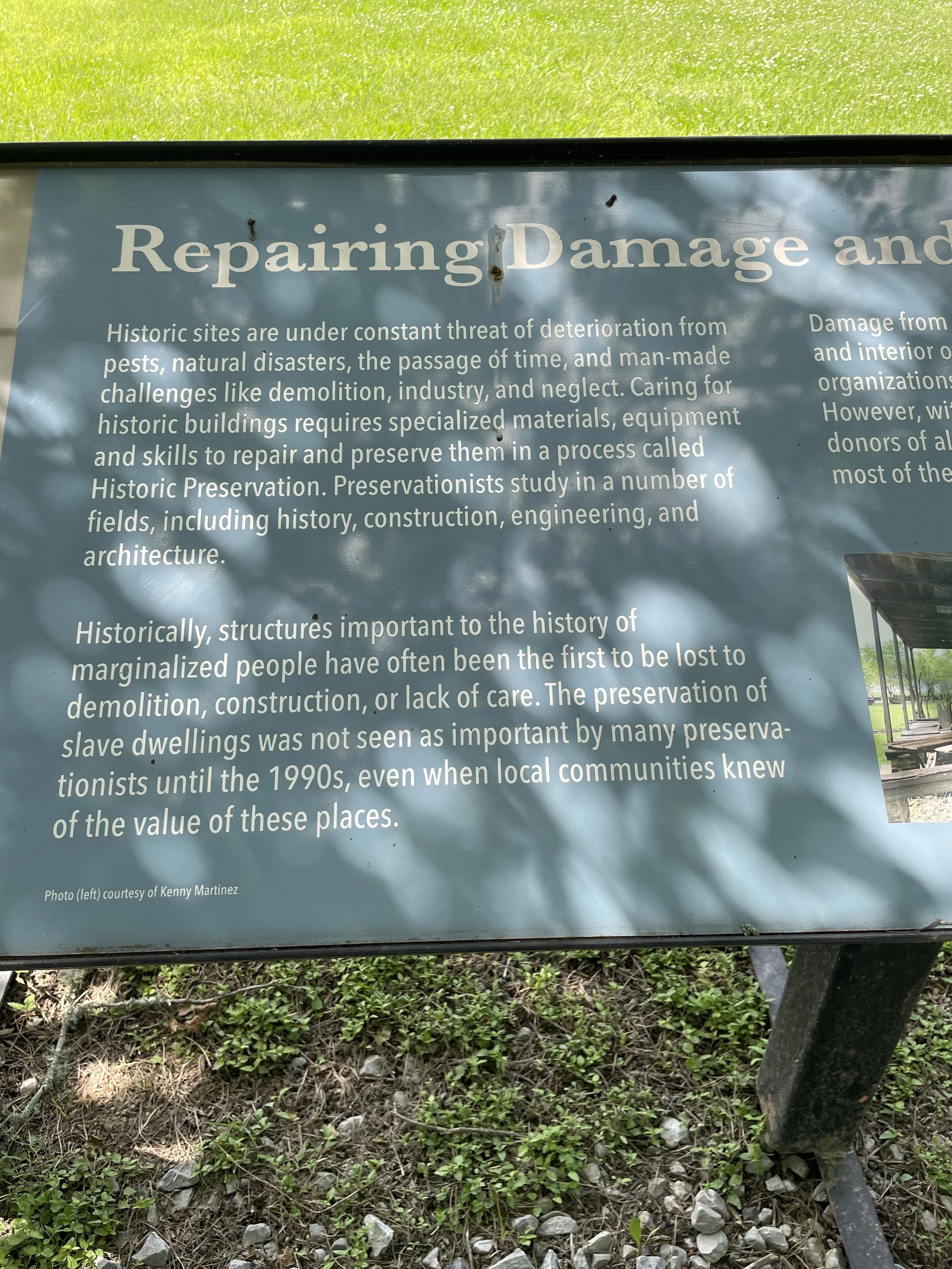

As you walk the grounds, the stark contrast between the enslaved people's cabins and the main house is impossible to ignore. The slave dwellings are small, cramped, and made from rough materials. There’s no insulation. In the brutal Louisiana summers, the heat must have been suffocating. In winter, the cold would seep through every gap. There was no comfort, no privacy, no rest.

These homes, if they can even be called that, were meant for survival, not dignity.

And then, just a short walk away, stands the plantation house itself. A grand, imposing building with white columns and wide porches, designed to impress. It faces the Mississippi River, proudly positioned so that every boat passing by would see its splendor. A showpiece of wealth built entirely on the backs of the people who lived in those bare wooden shacks.

This visual disparity tells the story plainly. The beauty of the main house depended entirely on the suffering of others. It is a structure of power, and of silence.

The Artist Behind the Faces: Woodrow Nash

The hauntingly beautiful sculptures you see throughout Whitney Plantation are the work of acclaimed artist Woodrow Nash. A self-taught African American artist from Akron, Ohio, Nash creates figures that are at once deeply expressive and reverently quiet. His work at Whitney includes dozens of life-sized clay and resin sculptures of enslaved children—figures based on real people whose names were recorded in the Federal Writers’ Project interviews with formerly enslaved individuals.

Nash’s style is unmistakable: elongated limbs, textured surfaces, solemn eyes that seem to follow you through the space. Each sculpture is placed intentionally—some inside the church, others seated on benches or standing near trees, silently bearing witness. They’re not behind glass or on pedestals. They live in the same spaces where enslaved people once stood, worked, and waited. That intimacy makes them all the more moving.

His art draws inspiration from 15th-century Benin bronze, African tribal forms, and European Nouveau stylization, resulting in works that are spiritual, rooted, and full of emotional gravity. At Whitney, his sculptures are not decorations. They are memory made visible. They are presence reclaimed.

You can learn more about his work at woodrownashstudios.com.

The Children’s Memorial

There is one place that broke me in a way I never expected—the Children’s Memorial.

Whitney is the only plantation that gives space to honor the lives of enslaved children, many of whom died before they ever had a chance to grow up. In a quiet garden, there are dozens of sculptures: small, haunting faces, created by artist Woodrow Nash. Each one represents a child who lived and died in slavery.

And in a separate, more secluded area—an unassuming open space surrounded by trees—stand the sculpted heads of decapitated children, marking the memory of the many atrocities committed here. This is not just symbolic. These are historical realities—documented, brutal, and often erased from public consciousness.

I sat in that silent space and cried. Not just tears of sadness, but grief, anger, disbelief. It was unlike anything I’ve experienced in a museum. It was a sacred silence, and I honored it.

The Church and Its Sculptures: Faith, Resistance, and Memory

The church at Whitney Plantation is more than a place of worship—it’s a space of profound reflection. While its small size may seem unassuming at first glance, the sculptures inside transform it into something far more powerful. These sculptures were created by artist Woodrow Nash, and they are deeply moving representations of the lives of the enslaved.

One of the most striking features of the church is a series of figures depicting the enslaved. They are carved in a raw, visceral style, capturing the depth of human suffering and resilience. These sculptures are not just artistic representations—they are symbols of the strength and faith that the enslaved people carried with them through unimaginable hardship. They show not just the pain but also the dignity, the unbroken spirit, and the hope that was cultivated in the face of oppression.

The church, as a space of worship, became one of the few places where enslaved people could find solace and strength. The presence of these sculptures speaks to the paradox of faith: a tool of control for the slaveholders, yet also a means of survival and resistance for those who were enslaved.

It’s in this sacred space that the enslaved people found a connection to something greater than themselves, a place where they could dream of freedom, even when that dream seemed impossibly distant. Standing among these powerful sculptures, you can feel the weight of their history—one of suffering, faith, resilience, and resistance.

Slavery Didn't End in 1865

It’s often taught that slavery ended with the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 or the 13th Amendment in 1865, but the truth is more complicated and far more uncomfortable. Slavery’s legal end didn’t mean the end of exploitation, violence, or systemic racism. Many plantations, including those like Whitney, continued to operate in deeply unjust ways well into the 20th century, with formerly enslaved people and their descendants still bound to the land by sharecropping, debt, and racial terror.

Whitney makes this very clear: slavery wasn’t just a Southern issue, or a historical footnote. It was, and remains, a foundational part of American history. The museum exists to center the voices of those who were enslaved, and to explore the ongoing legacies of slavery that still shape the United States today. From mass incarceration to systemic inequality, the echoes of slavery are not gone, they have simply changed form.

They Built This City

So much of what we love about New Orleans—its food, its music, its warmth—was created, preserved, and passed down by people who were enslaved. Their knowledge of agriculture, of cooking, of music and faith and family, shaped the culture we celebrate today. Their resilience became the rhythm of this city.

They are the heart of it.

An Invitation to Learn

If you’ve never been to Whitney Plantation, I encourage you to go. And if you can’t go in person, I urge you to visit their website, explore the Tilling the Soil podcast, and download their free Whitney Plantation app, which offers guided tours, historical background, and access to stories from the people who lived through it. Learning this history is not easy, but it is essential. This is not just about the past, t’s about who we are and where we go from here.

It’s not easy. But it’s necessary.

We cannot grow without knowing where we come from.

As always, thank you for being here.